Seasonal Book Recommendations for Winter 2025

Light was not an unalloyed blessing, nor darkness inevitably a source of misery

White Dog

First snow—I release her into it—

I know, released, she won't come back.

This is different from letting what,

already, we count as lost go. It is nothing

like that. Also, it is not like wanting to learn what

losing a thing we love feels like. Oh yes:

I love her.

Released, she seems for a moment as if

some part of me that, almost,

I wouldn't mind

understanding better, is that

not love? She seems a part of me,

and then she seems entirely like what she is:

a white dog,

less white suddenly, against the snow,

who won't come back. I know that; and, knowing it,

I release her. It's as if I release her

because I know.

Reading in a cold, dark world

Readers! It’s been a really long time since I’ve got my act together to recommend books to you. I’m so honored that new subscriptions keep coming in every week, even though it’s been over a year since I last made a peep.

My major undertaking this past year was to complete a first draft of my own book and sign with an agent, who ended up being the wonderful Erika Stevens of Salky Literary. My first revision of my manuscript is with her now—I’m sure many more revisions to come! An excerpt of the novel will be published in the Winter 2025 of The Kenyon Review.

So much has torn this world and my own heart apart in this past year. From my own city to Palestine, from this country to Congo and Sudan. And yet I live sheltered from so much carnage—political, ecological, social. Sheltered, but not separate nor absolved of any of it.

Reading is neither activism for nor abdication of this world, though of course it can play a role in either—and in any number of positions between. I wouldn’t dream of telling you books and reading will save us. But I offer you some of what I’ve loved reading when it’s cold and dark where I live.

Fiction

Lady into Fox by David Garnett

“He could see where she had rolled in the snow and where she had danced in it, and looking at those prints of her feet as they went in made his heart ache, he knew not why.”

I can’t honestly remember where I learned about this 1922 novella by a man better known by the nickname “Bunny”, and as a member of Vanessa Bell’s polyamorous Bloomsbury household. I do know it is one of the best books about partnership and marriage I have ever read, deeply queer and deeply wise.

This slender novella—well under 100 pages—is about a young married couple, very in love, who one day go for a walk in the woods. Somewhere along the way, for reasons they and we never discover, the wife turns into a fox. Lady into Fox turns the conventions of Japanese tsuru nyōbō (crane wife) or Celtic Britain’s selkies (seal wives) inside out. This is not the story of a wife who never was human but was either captured or transformed herself to attempt marriage to a human man that was doomed from the start. This is, to me, a much more familiar story: one about two humans who love each other very much, but then a change that neither of them could have predicted occurs, fundamentally changing the nature of their shared life.

This novel could be read as an allegory for so many things that happen to partnered people who truly want to make a life together and then find that life so different than they expected. Partnerships are changed by gender transition, shifting or newly discovered sexual orientation, disability, illness, aging, ideological conversions. To love one person over a long time, Garnett’s story shows, is, paradoxically, to love someone different than you fell in love with. And that loving partnership is based more in physical logistics than emotional feelings. Sylvia’s transformation into a fox calls upon Richard’s creativity to make their home accessible and responsive to her new needs: diet, personal hygiene, pastimes—everything changes.

Most profoundly, Garnett resists the idea that we have “essential selves” separate from our bodies. To have a changed body is to have a changed self. To love a changed beloved not as we think is best but as the changed beloved needs is love’s true—often unimaginably heartbreaking and always deeply transformative—work.

PS: The Carl Philips poem above makes me think so much Lady into Fox, but I also highly recommend pairing with WS Merwin’s poem of encantatory power, “The Vixen,”.

The Ice Palace by Tarjei Vesaas

“Questions shooting out and then hiding again. I don’t know: gleams and radiance, gleaming from you to me, from me to you, and from me to you alone—into the mirror and out again, and never an answer about what this is, never an explanation.”

Yet another beloved book of mine that I have the brilliant Three Lives & Co. bookstore in New York for introducing me to. It is a brief, strange, singular novel—one of the best accounts of queer girlhood I’ve ever read, written by a cishet Norwegian man in 1963.

The plot is spare and simple: Two little girls connect in an electric, ineffable way, recognize something in each other they don’t yet have language for. They are filled with “astonishment”—at what they have seen in each other, at the grandeur of the frozen winter world around their village, at the enormity of Being. Tragically and inexplicably, one of the girls dies. The other little girl has to survive this grief and loss, has to learn that it isn’t her fault, has to learn that it’s no one’s fault, has to learn to come alive to astonishment again.

The Ice Palace does not offer unmitigated “queer joy” (though joy does exist in these pages) any more than it offers tragedy as the wages of queerness/sin. It’s simply a story about how things that should never happen do happen, and sometimes they’re no one’s fault, and to be a survivor of the unthinkable is unbearable. It’s a book that takes childhood grief very seriously, and takes equally seriously the possibility of joy after grief.

PS: I love Sabrina Imbler’s essay on The Ice Palace, part of their Catapult series on sea creatures that eventually developed into How Far the Light Reaches.

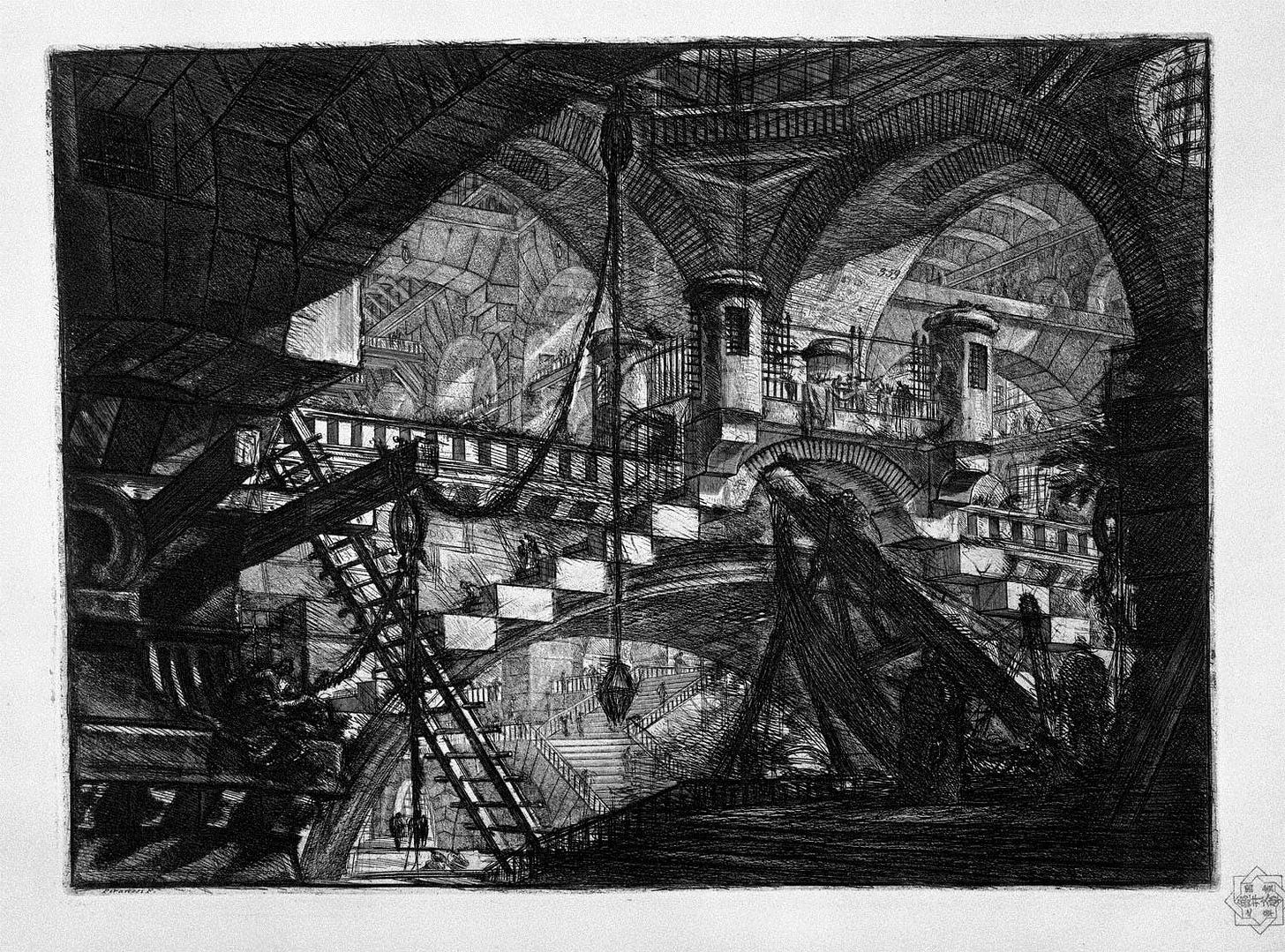

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke

“In my mind are all the tides, their seasons, their ebbs and their flows. In my mind are all the halls, the endless procession of them, the intricate pathways. When this world becomes too much for me, when I grow tired of the noise and the dirt and the people, I close my eyes and I name a particular vestibule to myself; then I name a hall.”

Like many people who read this sui generis novel during 2020, I was thunderstruck: how did Susanna Clarke known what the imposed isolation of a global pandemic would feel like before it ever happened?? The answer: because of 15 years of living with ME/CFS, in which, after the globally lauded publication of her enormous bonbon of a fantasy novel, Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, she all but disappeared from public life.

My own experience of chronic illness has been very dynamic—for about 25 of my almost-40 years, I’ve dealt with several chronic conditions that have gouged away years I’d rather have spent not-in-bed. For the past few years, these conditions have been in near-total remission, with occasional flares that, with dedicated care, have abated relatively quickly. If I were a different person, I might give you a simple explanation: changed hormones; profound alterations in work and living that I had the privilege and support to be able to make around age 30; something else equally made-up. Because the simple answer is: I don’t why, nor do my doctors.

The word so many people have used to describe Piranesi is “dream-like.” Which is in so many ways what it feels like to be living in mysterious remission from disabilities that were ill-defined and poorly understood and frequently sneered at by some in my life. I’m sitting here today at my desk, feeling really quite well (at least in my own body), and I think: Are you sure you didn’t make it all up? Surely, it wasn’t as bad as you made it out to be at the time. None of it makes sense. All things I might say about any bad dream.

Piranesi, like all embodied mysteries (of which illness is one) is hard to say much about. You kindof just have to read it. Yet, obliquely, this novel points to so much about what the loneliness of a body abandoned by societies and systems can feel like. There’s a lot of sadness in it, but everytime I’ve read it, I finish with a feeling of indomitable joy, a knowledge that we make ourselves at home wherever we find ourselves not because where we find ourselves is free of suffering, but because we are alive.

PS: Pair Piranesi with Virginia Woolf’s classic essay, “On Being Ill,” or Derek Jarman’s ecstatic “bedbound gardening” dreams in the later portions of his garden memoir Modern Nature.

Nonfiction

Woman in the Polar Night by Christiane Ritter

“No, the Arctic does not yield its secret for the price of a ship’s ticket. You must live through the long night, the storms, the destruction of human pride. You must have gazed on the deadness of all things to grasp their livingness.”

In the last few years before Nazi Germany annexed Austria, an Austrian woman, Christiane Ritter went to spend a year with her husband, Hermann, who had (very mysteriously! Never explained in the pages of this book!) been living near the North Pole for the past 3 years. Hermann wasn’t a “polar explorer” per se—more of a guy who liked living alone in extreme conditions.

There is definitely an angle at which I think this book is worth viewing askance: what is it about generations of Europeans obsessed with moving to a place where non-European people have built entire civilizations and cultures for millennia and then writing about what it’s like to live there like they invented doing so?

But here’s what I really love about this book: much like Lady into Fox, it’s a very unusual, and I think very necessary, portrait of marriage. As I indicated above, Hermann and Christiane’s relationship struck me as confusing, and she writes like my confusion about her domestic arrangements is none of her concern. I like that; it’s quite bracing to encounter in a memoir.

But more importantly and interestingly, this book is about how Christiane and Hermann made a life in a one-room shack with a young man named Karl. I’m fascinated by how many people writing about this book act like this is a minor detail. To me, it is central and exciting and important. This book is no solitary Walden, and it’s not even a book about a middle-aged romantic tryst at the end of the world. It’s a book about home and family-making, and about how much of any longterm domestic partnership is about people outside the two members of a couple.

Of course most of us who are married don’t live in one room with a friend so as better to protect each other from polar bears, but on a metaphorical level…maybe, at the best moments, that is what we’re doing? Karl, unpartnered and beloved, is a key part of this book—not as a pseudo-child or a third romantic partner, but as a friend.

And…I admit that Ritter’s descriptions of long nights in the wild frozen North are pretty great, too.

PS: An African in Greenland by Tété-Michel Kpomassie is a (surprisingly fun and sexy!) romp of a polar exploration book beyond the uninterrupted European gaze. So, too, (with some much darker twists) is The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley.

At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past by A. Roger Ekirch

“The darkness of night loosened the tethers of the visible world. Despite night’s dangers, no other realm of preindustrial existence promised so much autonomy to so many people. Light was not an unalloyed blessing, nor darkness inevitably a source of misery.”

One of my favorite history books ever—a treasure trove of hidden quotidian life and humanity borne from years of archival research. I read this book cover to cover, but very slowly. It lived on my bedside table for months, and I’d read a few pages right before going to sleep.

Night was, it turns out, frequently referred to in early modern Europe as the “night season”—an interesting deepening of the idea of “seasonal” activities. In particular, I love this book’s chapters on fire and on non-visual sense realities in early modern night.

There’s much in these pages about night as a site of rebellion, pleasure, and self-emancipation for many marginalized people: enslaved persons, serfs, servants, sex workers, disabled persons, and more. There’s also a lot that challenges any fondly held beliefs that pre-capitalist times were enormously equitable times, when, without exception, people lived at a gentler pace, more in touch with the seasons, and less exploited. You know who has always had to work long hours, losing sleep and leisure, even before “bosses”? Poor people. And you know who’s always been deeply ingenious and tireless in resistance to and in reinvention of the world? Poor people.

This is a must-read for dark seasons of all kinds.

PS: Pair this with any number of Louise Gluck’s bracing night poems; one of my favorites is “The Stars.”

Children’s Books

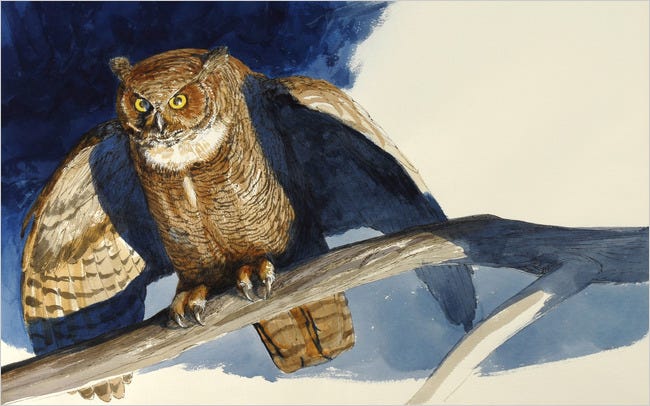

Owl Moon by Jane Yolen, illustrated by John Schoenherr

“We watched silently with heat in our mouths, the heat of all those words we had not spoken.”

I was born and spent the first 10 years of my life in North America’s Sonoran Desert—a few hours north of the US-Mexico border. It is an incredible ecosystem, a fragile one, and a landscape for which temperate zone ideas of spring-summer-fall-winter seasons do not apply. The Sonoran landscape speaks its own language of monsoon and desert bloom, long drought and brief flood.

I did not see snow until I was 6 years old. But even before I could read, and for years of my little life before and after I saw the first snow I can remember, Owl Moon obsessed me. The narrative thrust of this book is about a child going into the midwinter woods after dark—after bedtime—with her father in search of a Great Horned owl. The language is beautiful and simple; the illustrations even more gorgeous, with a moody, limited palette of lavenders, blues, browns, and blacks (Schoenherr won the Caldecott Medal for this book).

But it was the snow and the cold and the trees—hundreds of them, more than I had ever seen in the flesh—that made me read my copy of Owl Moon to shreds. There is so much longing, so much questing for a thing you’ve never even seen, in this book’s pages. When I close my eyes I can feel it still.

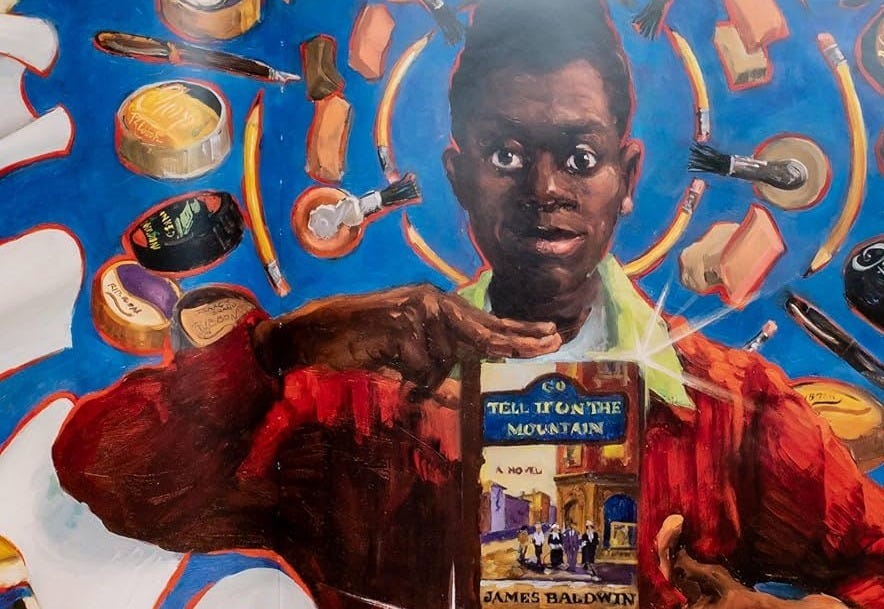

Go Tell It: How James Baldwin Became a Writer by Quartez Harris, illustrated by Gordon C. James

My friend and fellow Cleveland-literary-community member Quartez has been working on this beautiful picture book for so long and it finally published on January 7, 2025!

Quartez has been a Baldwin Fellow, deeply immersing himself in Baldwin’s life and work for the past few years, and this vibrant picture book wonderfully focuses on the formation and flourishing of a singular artistic vision. Quartez’ background as a poet and a 2nd grade teacher shine through on these lyrical pages, with gorgeous illustrations by Gordon C. James. If you order a copy from the title linked above, it’ll be signed by Quartez, and can even be personalized.

What I’ve been reading: Taiwan Travelogue by Yáng Shuang-zi; the electrifying forthcoming memoir Worthy of the Event by transfemme elder Vivian Blaxell; and the new Ali Smith, GLIFF, out in North America in a few months. I’m currently in the middle of Monstrilio by Gerardo Samano Cordova and Enter Ghost by Isabella Hammad, while slowly working my way through rereading Holy Feast & Holy Fast: The Religious Significance of Food to Medieval Women by Caroline Walker Bynum and reading (for the first time) Food in England by Dorothy Hartley. Savoring and drawing out as long as possible Sylvia Townsend Warner’s astounding fantasy story sequence, Kingdoms of Elfin.

What next: I just got the galley of The Emperor of Gladness, Ocean Vuong’s novel coming out in May. I’m eager to read Sour Cherry by Natalia Theodoridou and continue getting to know Nella Larsen with Quicksand. Nonfiction-wise, I’m hoping to tackle Bad Gays: A Homosexual History by Huw Lemmey and Tiya Miles’ Tubman biography that came out last year, Night Flyer.

I’m also working to stay sustainably connected and responsive to networks of people seeking to build a just world, trying to rescue what is good from oblivion. For me, this looks like ongoing relationship and care for LGBTQ asylum seekers through the Rainbow Initiative; the long-established, grassroots anti-carceral work of the Cuyahoga Jail Coalition, and the networks of care and advocacy nurtured by my local radical collective.

I’m so happy to get this!! I’ve added tons of these to my library list for this week. Especially those arctic ones…. Can’t wait.

So delighted to have this magic back in my inbox! ✨