cutting greens

by Lucille Clifton

curling them around

i hold their bodies in obscene embrace

thinking of everything but kinship.

collards and kale

strain against each strange other

away from my kissmaking hand and

the iron bedpot.

the pot is black,

the cutting board is black,

my hand,

and just for a minute

the greens roll black under the knife,

and the kitchen twists dark on its spine

and I taste in my natural appetite

the bond of live things everywhere.

When I started this newsletter almost 2 years ago, I aimed for it to be monthly, realizing how different the seasonal flavor—where I live—is from month to month. I wanted to help capture—no, to sing in harmony with—that via book recommendations.

But here I am, in this season of my life, writing to you at a frequency that seems more quarterly, which is how seasons are usually mapped onto my part of the planet. (And which people from my part of the planet have tried to forcefully map onto other parts of the planet…but that’s a story of its own.)

I’ve been struggling with reading myself lately. I’ve been craving ripping yarns told in simplest, sparest prose. Tell me a story. But in practice, when I actually sit down to it, the only reading I can seem to stick with is nonfiction, often very scientific biology and chemistry, often not even books, but papers. I suspect this is a slanting way of begging the same thing: tell me a story.

I’m particularly obsessed with what is happening in the trees around me right now, those parts of the plant world so present all winter and yet somehow absent, that will soon be returning to themselves with the vernal equinox.

The trees are starting to do something fundamental to treeness and invisible to the human bystander: they are growing in two directions at once. Botanically speaking, to be a tree is to have bark and heartwood, and, between both, a layer of cells called cambium, which means, in Latin, change. The cambium is an inner skin that is two potential futures. Its cells can grow out toward light and birdsong and rainfall, differentiating into phloem, the network of tube cells down which the sugars that leaves make travel all summer. Phloem cells turn over frequently, pushed ever outward to become a tree’s bark that is then sloughed off and sent back to earth, with little to show for their vast sweet work after a season or two. Conversely, cambium cells that grow inward, that differentiate into xylem, the tube cells that carry water and minerals up from the roots—these last in darkness for a tree’s whole life. Xylem cells harden and die and form tree rings, a record of flood and drought held fast in wood. Even when long-dead, they are the steadfast core around which and through which a tree lives and grows ever vaster, ever sweeter, ever more hospitable to ever more lifeforms.

All of this seems so relevant to my own experience of living, to being a self, that I fear belaboring the metaphor. I just want to tell you the story of the tree’s two selves and tell you how familiar this all sounds: the outward-growing, quickly changing, here-and-gone growth, so full of sugar, right alongside the hidden, inward-moving, hard growth that leaves an everlasting trace—no, not just a trace but a holdfast—the very core of holding up the softer, sweeter parts. (Before you ask: yes, I am reading How I Became a Tree right now and would love to know what you think of it!)

An Announcement: A Thousand Ways to Pay Attention: Discovering the Beauty of My ADHD Mind by Rebecca Schiller, one of the most seasonal reads I know if I do say so (and did edit it) myself, is out in paperback this week in North America. You probably know the drill: I love it so much, it changed my life, I hope if you’ve been waiting for a more affordable price point, you might want to buy a copy now!

And now, some book recommendations, which I have arranged to reflect my feeling of how they go along with the unfolding of Spring, from earliest to latest:

Birdsong by Julie Flett

“Still, from her bed, we can hear the spring birds singing their songs. And the tickle of the branches against her window.”

I always think of this as a quintessentially early spring book. Then I pull it out and wonder why I thought that since it takes place across a whole year. And then I remember that’s its genius: it’s about the yearlong work that goes into making spring, making the birds’ return possible, making life rise up again.

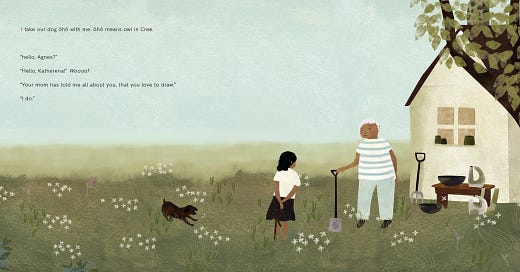

It’s about a little girl’s unfolding friendship and loving care (from and for) an elderly neighbor. Little Katherena teaches her new neighbor, Agnes, Cree words and moon phases; Agnes teaches Katherena how to make compost and how to make a whole field of snowdrops from one little clump contained in a teacup.

More than anything, I think this book is spring to me because it refuses simplistic mapping of simplistic seasons onto complex human lives. There are new beginnings and there are futures not just for children, but also for elders and chronically ill people. Birds return not just to the garden, but to the sickbeds where the people we love come to be visit and listen at the window beside us.

Slime: A Natural History by Susanne Wedlich

“All multicellular organisms grew up in a microbial world, and we need a facilitator for our relationship with them — which is slime.”

I’m so thrilled that this wonderfully idiosyncratic science writing, originally written in German and then translated into English in the UK is now available in North America as of last month. It is wide-ranging and difficult to categorize as slime itself.

As much as we think of water as the prerequisite to life on earth, there is, I learned from Wedlich, a very important caveat: as long as water is harnessable as slime. Because in all its different forms, that’s what slime is: almost always ~99% water, but water harnessed by molecules that can hold it in soft suspension so it doesn’t evaporate too quickly or run away too fast. Slime is water held in check, but gently enough that it can still be water.

Wedlich is as interested in slime as a human idea (see: her chapter on Lovecraft’s evocation of slime as metaphor for his racist contagion anxieties) as she is in various slimes as a bedrock (ha!) to biological human and other life. This book, like slime, is wide-ranging and multifaceted. Slime is expansive, slime is queer, slime is liminal, slime is everywhere, slime is life.

The Makioka Sisters by Junichiro Tanizaki

“The ancients waited for cherry blossoms, grieved when they were gone, and lamented their passing in countless poems. How very ordinary the poems had seemed to Sachiko when she read them as a girl, but now she knew, as well as one could know, that grieving over fallen cherry blossoms was more than a fad or convention.”

The good news: this novel is, in all the best ways, unlike almost any other novel I’ve ever read. The bad news: this novel is, in all the best ways, unlike almost any other novel I’ve ever read, and that is disappointing because I want to read more things like it so badly.

Originally published in serial form, this is the minutely detailed saga of a family of sisters over the course of a few years—two married with children, two unmarried. It’s set in Japan just as World War II is about to rip across the entire world, but that is not the focus of the book, since it was actually written and published while WWII was still ongoing (and in the aftermath). Here, War is not motif; it is part of an unfathomable and incomprehensible unfolding present.

In many ways, this is a book about women when men are not around. And astonishingly (to me), it is written by a man. It’s also minutely concerned with the texture of embodied physical life and dailiness which is all I want out of domestic fiction and where it so frequently disappoints me. “Domestic,” when applied to fiction often means only the kind of interpersonal relationships described, and not all the other stuff: food, weather, religious observance, illness, clothing, chores, crafts, and decor. I love huge, thick novels that tell, in detail, how people set their tables. Or, as so movingly changes from year to year in this book, how a family packs to travel together to go see the cherry blossoms in Kyoto. Don’t get me wrong: there are all kinds of intricate human relationships here, it’s just that I believe them so much more when all the other trappings of life are included.

Try this one if you love Proust or Ferrante’s Neapolitan Quartet or Big Russian Novels, but also if you don’t like any of those, because there is so much here to love.

The Salt Eaters by Toni Cade Bambara

“There’d been a dog with a nasty gash on the back of its neck. That had stopped her, fixed her to the spot. That was the moment she formed the words: ‘I’ve come to the marshes. I’ve just seen a man in gumboots. I’m looking at a wounded dog who is looking back at me.’ As if it had waited for her to catch up, to find the place in the script, the dog paused and then dropped down of a sudden and wallowed in the mud close to the shallows. And she’d been humbled watching it. A nondescript dog, wounded, come to the place to heal itself in the earth.”

I actually bought my copy of The Salt Eaters on the same bookstore trip when I got The Makioka Sisters and read one avidly after the other last August thinking of both: This is a spring book.

The Salt Eaters, Toni Cade Bambara’s most famous novel, is actually an almost-summer book, a May or early June book, by my subjective seasonal compass. It’s about how people—specifically Black women who poured their entire selves out for the US Civil Rights movement—keep living when they realize they’re not going to win the struggle in their lifetimes and they still have plenty of lifetime left. And that maybe the struggle wasn’t even what they thought it was in the first place.

It’s about where abundance can be harvested when not all the seeds you planted sprout. It’s about women building coalitions for liberatory work. It’s about the unspeakable intersections of racism and poverty and colorism and racism. It’s about “mental illness” and suicidality not as pathologies but as logical reactions to a pathological world. It’s about seeking healing close to home. It’s about, in many subtle ways, the Black Outdoors (per Moten and Hartman).

“Dispossessed, landless, this and that-less and free, therefore, to go anywhere and say anything and be everything if we’d only known it once and for all. Simply slip into the power, into the powerful power hanging unrecognized in the back-hall closet.” (An evocation of outsider power that, with its closet reference, rings wonderfully queer bells for me).

I've always loved the sound of the words 'xylem' and 'phloem'! Very interesting to learn about the two directions of growth and I love the way you've described it. Slime sounds fascinating...

Thrilled to see Slime on this list!